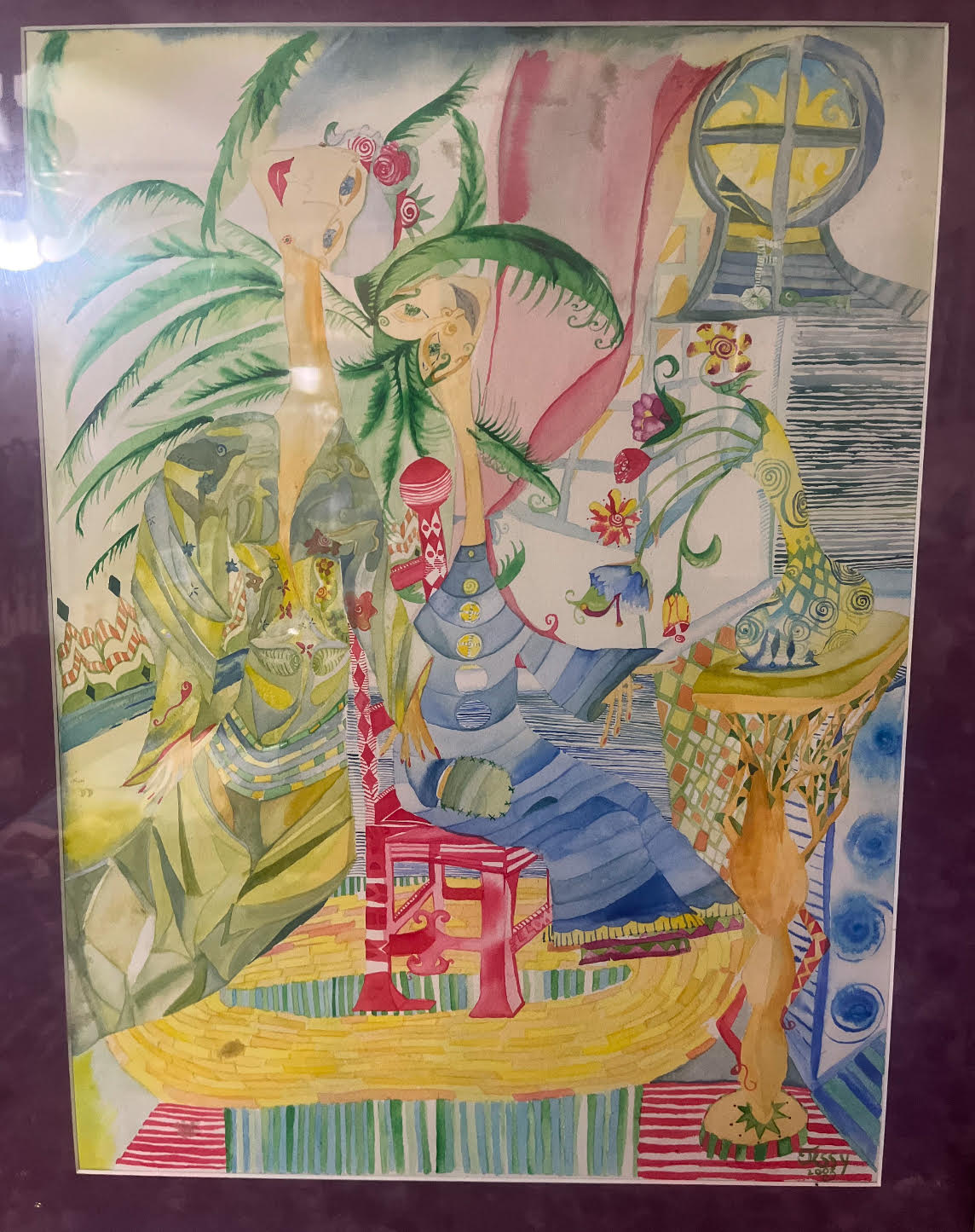

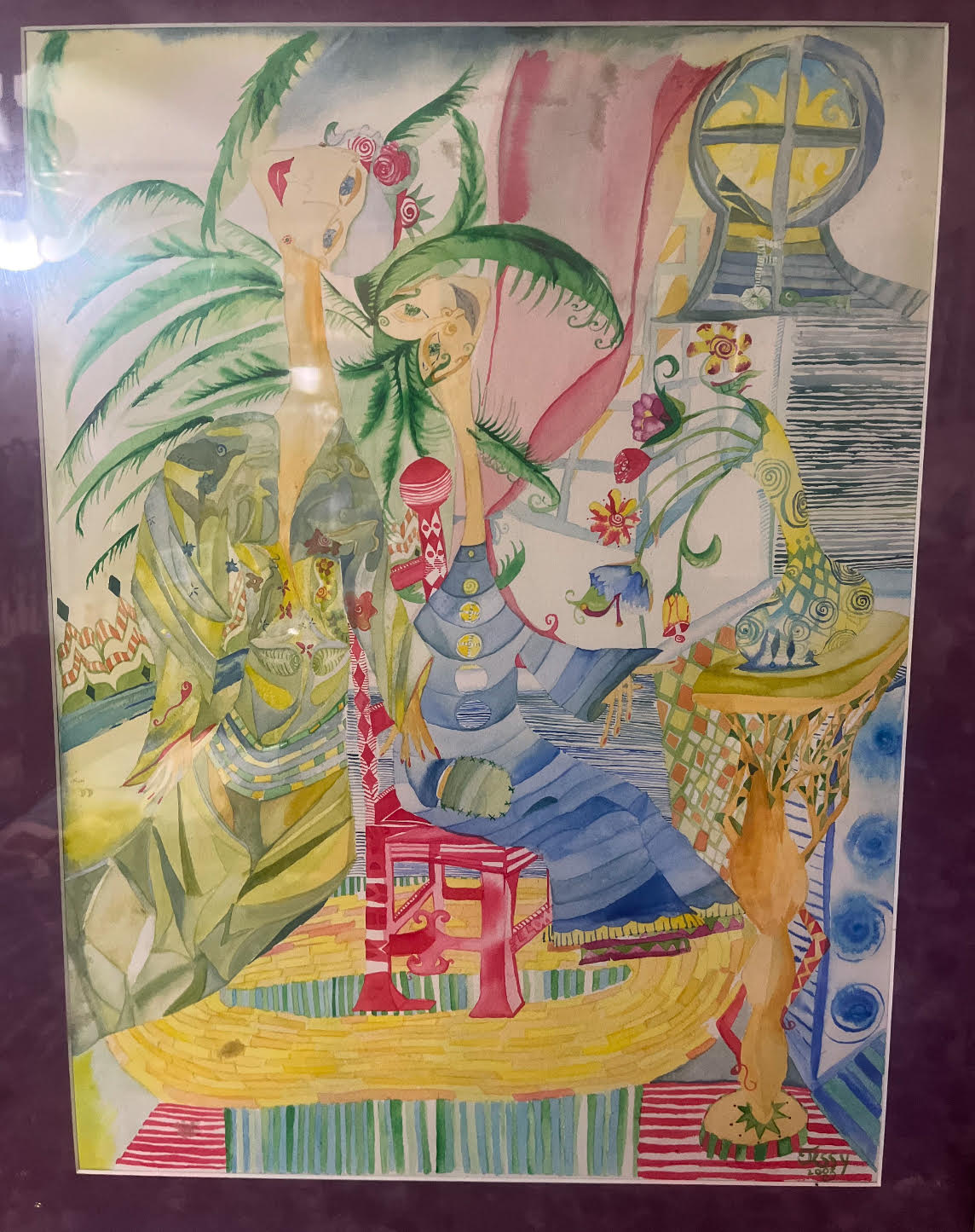

Teresa DiFalco and the legacy of Surrealism

Italian painter Teresa DiFalco provides her insights on her chosen artistic style, Surrealism. This unconventional style of art, which disregards the conventions of traditional realism and contemporary styles, is the medium that DiFalco most resonates with. Surrealist artists such as DiFalco let their unconscious minds bloom through cinema, art, and literature, weaving intricate techniques to chart the clockwork of dreams and the labyrinth of the inner psyche.

DeFalco’s pieces are inspired by the works of many well known artists known for their defiance of convention and embracement of the absurd.

“My love for art doesn’t only extend to one or few artists in a certain medium, rather to a variety of innovative creatives who’s art inspired me to create on my own. For example, I fell in love with the artist Chihuly, an artist who specializes in colorful, irregularly shaped statues made of blown glass. Banksy, the famously elusive graffiti artist who put so much meaning behind even his most simple of works, is another,” Di Falco said. “Even Craig McCracken, the animator behind the style and depictions of the hit children’s cartoon “The Powerpuff Girls” is someone who’s become a source of continuing inspiration to me.”

Knowing the artist behind the art is an important factor DiFalco takes into consideration when examining her favorite works.

“The feeling that comes with studying a piece of artwork and trying to understand every little detail of what I’m looking at is especially enjoyable when I’m trying to connect it to an artist’s own thought process and psychology,” DiFalco said. “What I love most about art is that it’s a way for someone to connect with other people in a way that can’t be expressed through words.”

Before DiFalco involves herself with creating a piece, she must make sure that the atmosphere around her is an environment that she can completely relax in. For DiFalco, the process of setting up her work is just as important as the work itself.

“I must set up a situation for myself where I have everything I need to become absolutely enraptured into my art,” DiFalco said. “I need a fun beverage–preferably a hot tea–and a soundtrack that I can anticipate will carry me into the mood I want to feel while creating.”

Di’Falco’s art is often a product of free-form expression, a commonly used technique used by Surrealists where an artist spontaneously draws whatever comes to mind to create a final, coordinated piece.

“Every time I decide to do anything creative, I like to “lose my mind”,” DiFalco said. “What I mean by this, is that when I’m creating something, I want to be able to become completely immersed into what I’m doing so much that my work becomes like a form of play. When my mind is cleared of burden, I draw whatever comes to me, as I believe it to be the purest form of self expression.”

Throughout her life, Teresa’s art is a reflection of the developing inner workings of her mind as she grows from a teenager, to young adulthood, to her middle age.

“My artwork has always been a testament to my maturity as a woman. I’m able to look back and observe my old pieces and become reminded of the feelings I’ve grown from or carried with me into my adulthood,” said DiFalco. “Age and time have always been concepts in particular that I’ve been fascinated with ever since I began my journey as an artist. When I was a teenager I’d create art to better understand the complexities of adulthood–how one day I would become this enigmatic grown being who’s behavior I could hardly even begin to comprehend. Once I found that I’ve become a woman, my focus shifted onto the concept of aging itself. I’d ask questions such as, “how will my mind change from now, to then?” and I’d incorporate those questions into my art.”

Staying true to the concept of Surrealism, DiFalco’s paintings often explore the contradictions and complexities of the past experiences that have transformed her psychology.

“Through my painting, “Why do we Hello?” I express my confusion with why people connect with each other if ultimately, we only cause each other sorrow,” said DiFalco. “Whether it be through grief, betrayal, or heartbreak, there is no good ending to a human relationship, so why do we continue to seek the company of others?”

Proceeding the devastating events of World War I, Surrealism emerged as a response from traumatized creatives who, in a time where understanding and sense were sought by many, explored their own innermost psychology to process the traumas of war and corruption. Ironically, this introspection gave rise to one of history’s most visually nonsensical art movements.

This movement, which began in the 1920s, touched nearly every aspect of art, from painting and literature to film and sculpture.

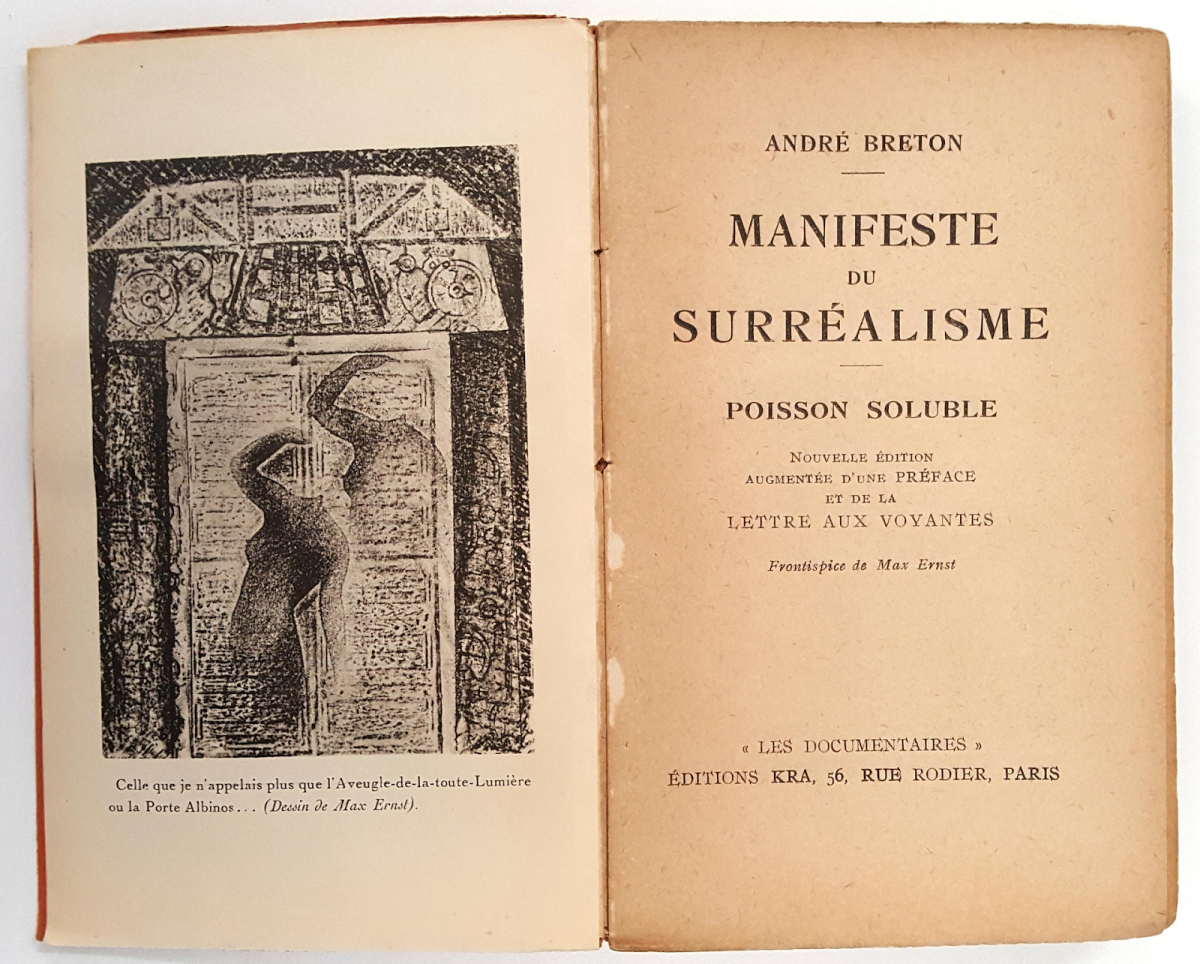

Surrealism’s beginnings were officially set into trajectory with André Breton’s 1924 manifesto, “Manifeste de Surrealism” , the movement being described as “the systematic illumination of hidden places” in the psyche. The style drew its inspiration from Dadaism—an earlier, similar artistic movement that also rejected the conventions of society—Surrealists sought to explore the unconscious mind through various alternative and often unconventional psychological mediums such as automatic writing, dream analysis, and most importantly, free-form artist expression. The Bureau for Surrealist Research, which was established in the same year, collected dreams and documented behaviors to deepen their understanding of the subconscious mind.

Popular poet and art critic, Guillaume Apollinaire contrived the term “Surrealism” himself. His influence combined with the time’s most famous philosopher Sigmund Freud’s groundbreaking theories on the unconscious mind, propelled artists into questioning reality itself as well as incorporating the dream-like and bizarre into their work. Artists were offered a new canvas to explore their deepest thoughts and emotions through Freud’s ideas on dream analysis and the repressed psyche.

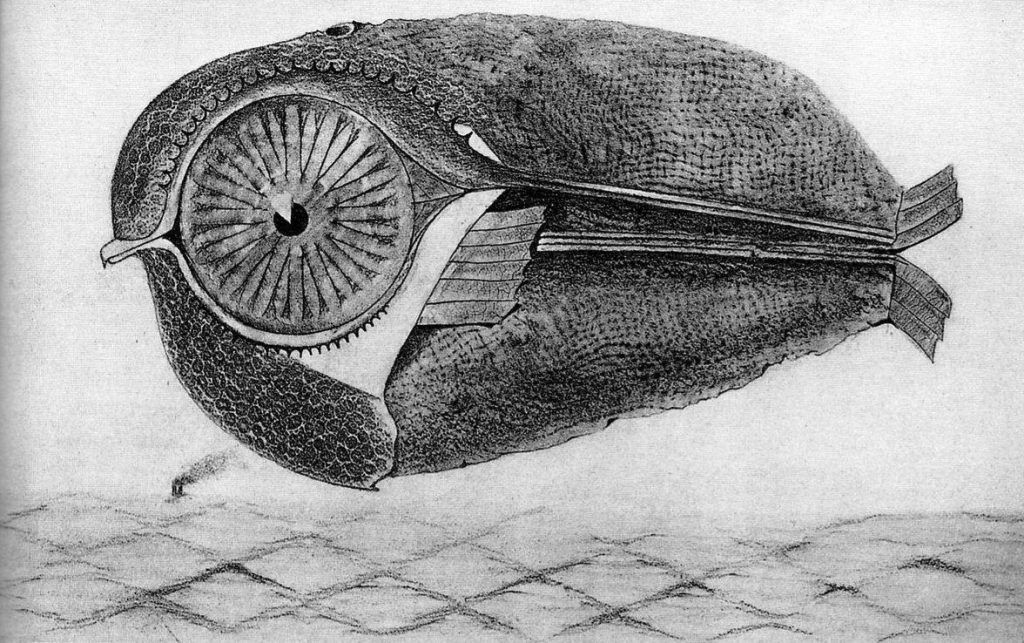

Alternative psychological techniques were often experimented with by Surrealist artists such that they would be able to access the unconscious. Automatism, for example, was the most popular technique where artists would be able to allow themselves to create without conscious thought. Max Ernst used “frottage” as a form of automatism, which involved rubbing graphite over textured surfaces in order to create unconventional shapes and pictures. Ernst would use these shapes as blueprints to develop into strange, corporal imagery. Similarly, Joan Miro would create a series of spontaneous markings and structures before transforming them into his next piece, expressing a sense of childlike freedom and intuition.

One of the most famous names in surrealism as well as in art history is Salvador Dali. He described his artistic method as “hand painted dream photographs”, where he would distort the lines between reality and illusion through creating immersive, realistic images of impossible or absurd scenarios. He believed that Surrealism provided a method to confront the irrational and the strange, calling his process a “paranoiac-critical method,” which was where he would deliberately send himself into a paranoia such that he could see the connections between unrelated objects. Through his methods, Dali was able to invoke a sense of deeper psychological meaning behind his paintings that most other artists at the time had always ignored.

Despite the male dominated field at the time, women played a crucial role in Surrealism, some of the most influential female artists emerging from the movement. Frida Kahlo, despite sharing it’s ethos, rejected being labeled as being a part of the movement, stating, “I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.” Kahlo’s technique was deeply personal; she would combine her meticulous, heavily detailed brushwork with symbolic imagery that would represent her life experience and psychological manifestations such as her emotional struggles, physical pain, and her Mexican heritage. Kahlo would create with bold colors and flattened perspectives, making her pieces reminiscent of traditional Mexican folk art. She would repeatedly paint self-portraits to reflect her connection with her self autonomy as well as dreamlike compositions which painted a mirror to her subconscious exploration of identity and trauma. Kahlo emphasized that her work was rooted in her lived experiences, rather than in imagined fantasies.

Dorthea Tanning, another notable female figure within the surrealist movement, specialized in creating spatial ambiguity within her oil paintings and sculptures–doors opening to enigmatic fantasy realms, figures and images impossibly merging with their surroundings–changing the perspectives of many on how to visualize the hidden aspects within the human experience. Often, the figures in her paintings and installations depicted women. Tanning’s most prevalent theme within her work was challenging how society views the roles and representation of women versus the actual experience of being one, reinforcing her art as a dialogue between conscious reality and the real experiences within it.

The surrealist movement extends beyond the confines of paper and canvas. Cinema, sculpture, and literature are all mediums that have been touched by the movement’s influence. André Breton and Philippe Soupault’s Les Champs Magnétiques, 1920, pioneered automatic writing.

In film, directors like Luis Buñuel pushed boundaries with works like The Seashell and the Clergyman, 1928, blending irrational narratives with provocative imagery.

Surrealist sculpture embodied the movement’s ethos by manipulating everyday objects into bizarre forms. Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone,1936, exemplifies this playful yet unsettling approach.

Although the movement waned as an organized group, Surrealism’s principles continue to influence art, literature, and pop culture. Its emphasis on exploring the unconscious paved the way for modern art movements like Abstract Expressionism and Absurdism. Contemporary artists and filmmakers, inspired by its themes of juxtaposition and the dreamlike, keep its spirit alive.

Surrealism’s ability to challenge perceptions and provoke introspection ensures its relevance. Its works, from Dalí’s melting clocks to Magritte’s enigmatic imagery, remain timeless symbols of human creativity and the mysteries of the subconscious.

Surrealism was more than an art movement; it was a revolution in thought and expression. By daring to explore the hidden depths of the human psyche, it reshaped the boundaries of art and continues to inspire generations of creators worldwide.

Surrealism Art – A Deep Dive Into the Surrealism Art Movement

“Surrealism Art – A Deep Dive Into the Surrealism Art Movement.” Art in Context, October 11, 2024. www.artincontext.org/surrealism-art/. Accessed December 13, 2024.

Surrealism History ‑ Art, Definition & Photography | HISTORY

“Surrealism History ‑ Art, Definition & Photography.” HISTORY, A&E Television Networks, August 21, 2018, www.history.com/topics/art-history/surrealism. Accessed December 13, 2024.

“Frida Kahlo.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/biography/Frida-Kahlo. Accessed December 14, 2024.