Before reading anything, even skimming, picture a homeless person. Now, use three adjectives to describe them, whether it be their appearance, character, even scent. I go to a generally wealthy school district, Frisco Independent School District, I’m currently taking three AP classes, I have a considerably high grade point average, I smell like vanilla and this year I was homeless for three months. Now reflect: Do the adjectives used to describe me and those to describe your imaginary homeless person match? I would assume not.

As a teenager, it is so easy to lose yourself in your environment. Every friend, neighbor and even conversation gives you an idea of what people think about you, and after time it’s easiest to fall into the stereotype that you’re grouped into. It’s almost standard for teens to succumb to trends and change their hair, style and vocabulary to fit into a stereotypical high school group. However, there is nothing as gratifying as rejecting stereotypes and becoming the most honest version of yourself. Even in the face of adversity and extreme uncertainty, you can still be certain about yourself.

On the first of January, my father woke me up frantically, trying to pick up my mattress as I was sleeping on it. Within three minutes, I was out the door, walking my dog and myself to a friend’s house. I don’t even remember what I thought, and I seriously doubt that I was thinking anything coherently. Within that week, my family, my dogs and I were homeless. This experience alone, without undergoing homelessness, changed my view of homeless people. They were no longer smelly or lazy, they were just an idea of a person that I made up.

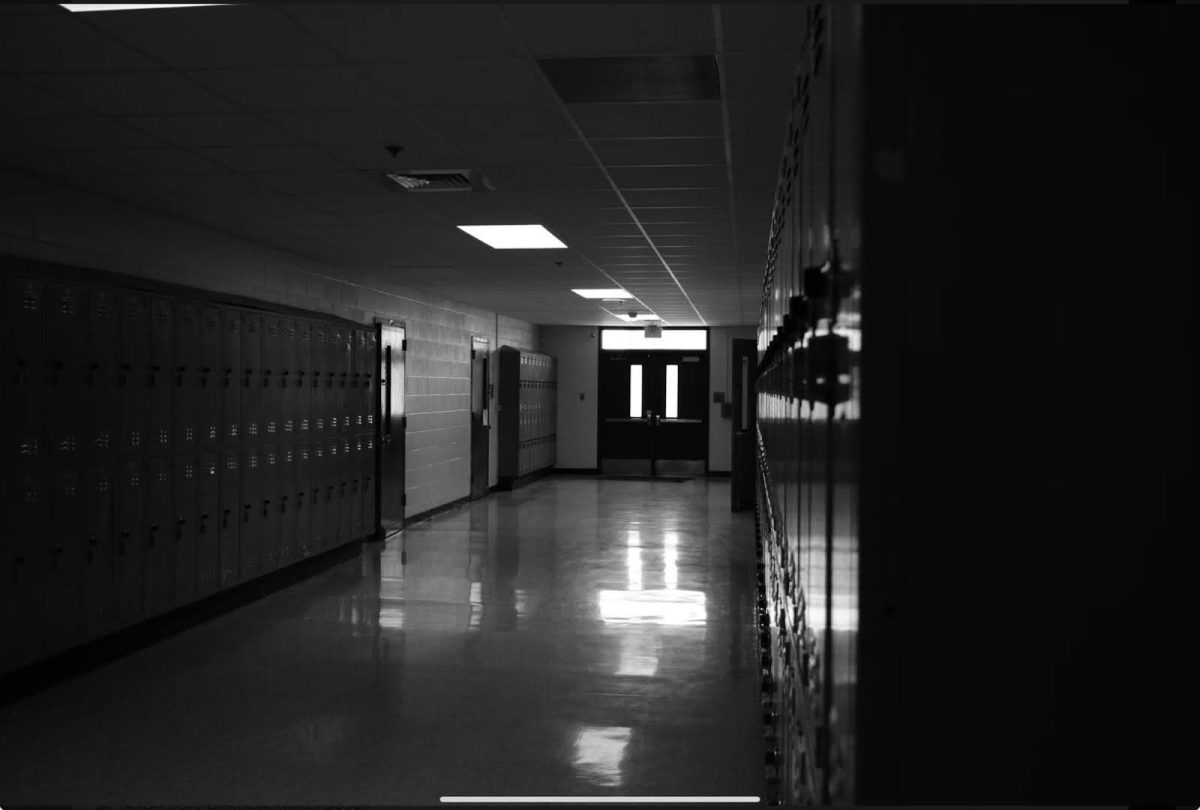

When I told my friends, their shock mirrored mine. However, it was more of a clutch-your-pearls reaction than anything else. When I talked freely of my housing situation, the room would go silent; I’m not sure if people wanted to eavesdrop nonchalantly, or if they didn’t want to say the wrong thing, but the silence that followed was paralyzing and isolating nonetheless. This made sense, though; the only version of homelessness that the majority of my peers have seen is that unshaven and stinky guy that lives in a box down the street. There’s also the immediate thought of “What did they do to get here,” that anyone thinks after seeing a homeless person. No one knew how to respond to me, because my homelessness was not my fault. I was simply a teenage girl who was the sum of her parents’ decisions; it wasn’t an action of mine that made me homeless, but people don’t know how to respond to things that they’re not used to. I was immediately grouped into a stereotype that I knew wasn’t me. However, the more that I was perceived as an unintelligent, unhygienic, unhappy homeless person, the more I allowed myself to become that stereotype.

Homelessness was isolating by itself, but the taboo sting in the air when it was brought up added a new and worse feeling. Living in Frisco, so many privileges are normalized and go unappreciated; random 16-year-olds get brand new cars that they take on joy rides to go on shopping sprees, all without having a job. I truly wish that you could see the look of terror on my peers’ faces when I told them about being homeless, because they are so desensitized to the privileged lives that they lead. So, not only did I feel alone, but I felt like I was constantly being judged for having or even being less than other people. Even when people asked me to reach out if I needed help, it only reminded me that people were better off and I was at least 10 steps behind them in life.

My peers began to look at me and treat me differently, yet the only thing that had changed about me was my housing situation. My friends would get uncomfortable when I talked about my day simply because it included some story that only happened because I was homeless. Can you imagine someone else not being able to stand talking about your day-to-day life? In short terms, I felt like a loser. The funny thing, though, is that homelessness is not uncommon. About one in 30 high school students go to school with no home to go to afterwards. With that statistic, it could be assumed that about 59 students at Emerson High School are homeless. Yes, homelessness is bad, but it shouldn’t be a taboo subject; homelessness is someone’s life, actually it could be 59 of your peers’ lives.

So, I separated myself from my homelessness, or at least the stereotype of homelessness that consumed me. I continued to come to school, bathed and ready to learn; I had to make myself seem the opposite of what I was perceived to be. Although homelessness–nor other people’s ignorance–is my fault, it was still thrust upon me as an issue to correct. I became the example of homelessness that people had access to, and if there was any hope in destigmatizing my situation, I couldn’t allow myself to fall into a stereotype. The less control that I gave to my situation and to my peers in deciding who I was, the happier and more genuine I became. You are more than what you are perceived to be, but it’s up to you to prove that to yourself and everyone whoever may doubt that.